Over the past two years, the community gardens I manage have become a haven for homeless or underemployed men and women. The pleasant setting attracts visitors from the surrounding, drab neighborhood, especially since, in Spring, 2022, the city closed their old haunt, a park five blocks away.

The garden grounds have some tall, leafy trees, a nice lawn, gardens full of vegetables and flowers, a large, shady pavilion, electric outlets to charge their free phones and a hose from which to drink water or with which to shower or cool off. The police look the other way as crew members hang out, consume many 24-ounce Bud Ice cans and plastic liquor bottles, use various drugs, take naps and piss wherever.

And that’s just the women.

OK, it’s just the men. At least when I’m there.

Most Garden Club members are chill or listless; It’s not always clear where that line is. A few are friendly. They seldom display hostility toward each other, and never toward me. Others are standoffish or odd, but that’s true of those who live in all kinds of settings.

One morning this week, when I arrived at the gardens at 7:30 AM, I saw one man sitting and another, who was wearing a shirt with broad horizontal blue and white bands, standing under the pavilion. There are usually three to six people there at a time, so the day was trending toward normal.

I walked to the back gardens 100 yards away, let our 19 chickens out of their coops to forage, gathered their eggs and fed them the much-appreciated remnants of a watermelon. Then I fetched my tools and giant marigold seedlings and walked back toward the front gardens with a Mexican gardener, Angelica, nearly 50, who speaks loud and fast Spanish and works very hard. As her phone blared bachata music from the old country, we danced a little and began planting hundreds of seedlings thirty yards from where the man in the banded shirt stood.

Taking my eyes off our work twenty minutes later, I looked over and saw the man lying on the ground. I thought nothing of it; people routinely recline on the ground beneath the pavilion. I suspected he was either sleeping, drunk or hungover.

When the grass-cutting guy, a husky Caribbean named Taylor, arrived ten minutes after that, he called out loudly at close range to the supine man, trying to awaken him. As Taylor was unable to rouse the man, he called over to me and told me the fallen man seemed to have stopped breathing. I walked ten seconds to the pavilion, where the man laid on the ground. With a whitening beard and his eyes shut, he looked around 50. Standing next to him, I saw no motion in his ribcage, and his arms were oddly splayed. Using his foot, Taylor twice forcefully nudged the man’s foot. The man didn’t stir.

Taylor called the police. Within minutes, the police and several ambulances arrived, sirens wailing. They asked Taylor and me what had happened and we told them. They surrounded the unresponsive man. I returned to plant more flowers. For at least fifteen minutes, they CPR-ed him. Then they covered his body with a sheet, moved him into the ambulance and drove away. When I finished my shift, I saw a hypodermic needle near our storage shed. I’d found other needles on other days.

The next day, Calvin, one of other guys who hangs out there, and with whom I’m friendly, told me, unsurprisingly, that the fallen man had died of an overdose.

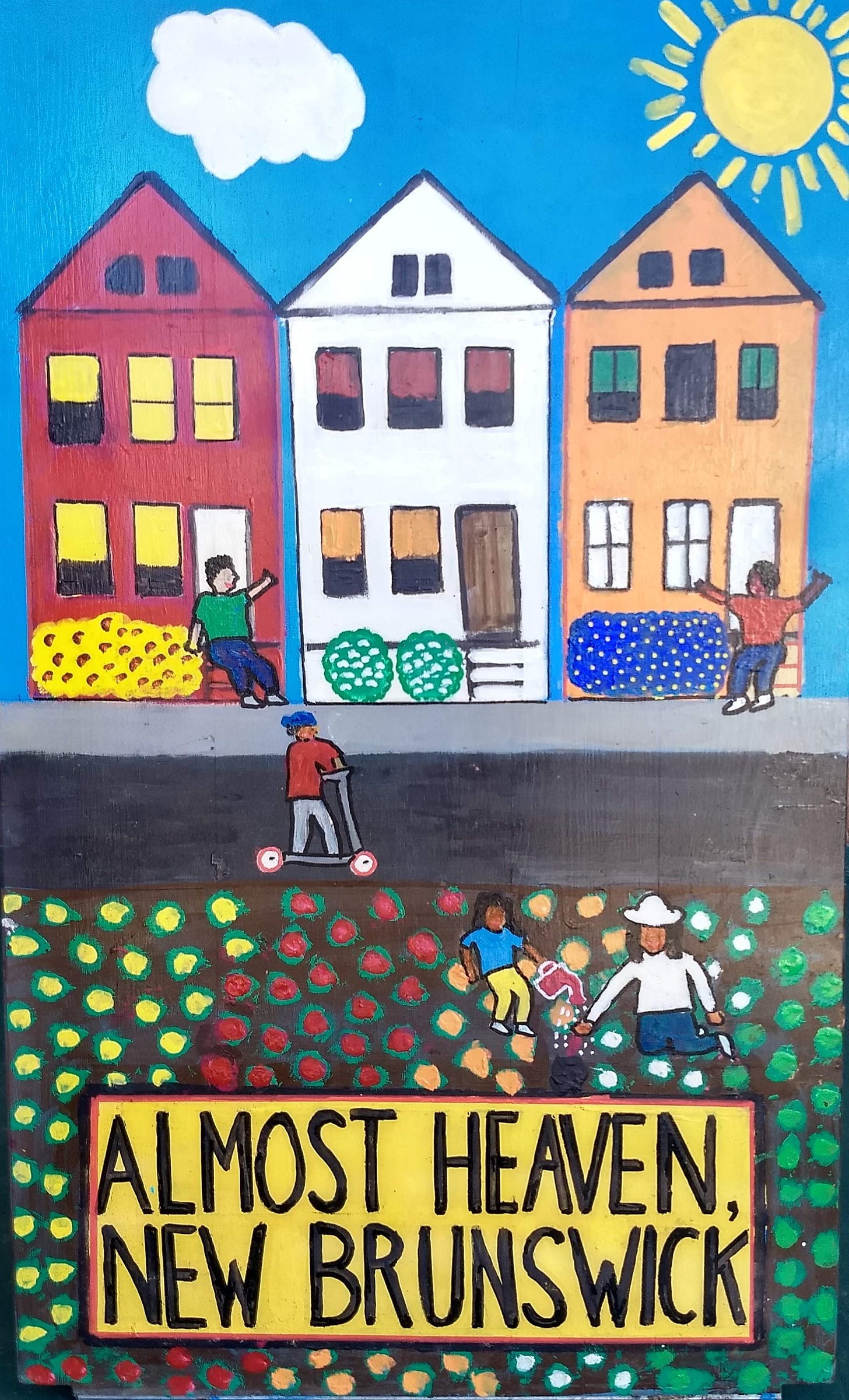

The ground on which he passed from this world was directly below a 2’ x 3’ folk-art plywood painting I had done and has, for two years, been fastened, at eye level, to a pavilion post.

I’ve previously been near strangers who had just died. I saw a man shot and killed in New York City and stood over his body as he quickly, stilly and silently bled out into his buttoned, short-sleeved white shirt. I’ve seen 7 and 12-year-old boys pulled out of water, dead, in two separate drownings. I’ve visited multiple familiar people on their deathbeds. I’ve seen dozens of people that I knew, or that people I knew had known, laid out in funeral homes. If you’ve lived long enough, you’ve had similar experiences, perhaps more than I’ve had.

Regarding the deaths of strangers—except for kids, whose deaths are lastingly awful—out-of-sight, out-of-mind applies in force. If, instead of being near the man who died this week, someone had told me that he had died of an overdose inside an apartment in the surrounding neighborhood, I wouldn’t have given his death much thought. They say that many people OD these days. During the first year of the Scamdemic, American overdose deaths increased by 30%, to over 100,000/year.

Seeing this man die at the gardens made me think more about deaths that we don’t see directly, and deaths of people we don’t know personally, and our reactions to such deaths.

As most Americans die behind closed doors or in hospitals, many people are unfamiliar with, and freaked out by, death. But, of course, death happens on a mass scale every day. Before March 15, 2020, 7,542 Americans died daily; worldwide, 166,342 did. The latter amounts to two deaths/second. Most Americans deaths occur past 70. Despite the deaths of some, life goes on, as it must, for the over 8,000,000,000 global citizens, including 332,000,000 Americans.

Before Coronamania, people weren’t sad about people dying natural deaths at old ages unless they knew the decedent. If people mourned all of the elderly strangers who died of heart attacks, pneumonia or the flu, they wouldn’t be able to function. They’d be sad every minute of their lives. And then they, themselves, would die. And if no one died, there wouldn’t be space for new people, or any urgency to life.

Somehow, during the Scamdemic, this changed. Politicians and some commentators frequently recited that “every death is a tragedy.” I’ve visited more than enough people in nursing homes to disagree with that notion. Human bodies wear out. As they do, pain and emotional suffering set in. Denying that process is like denying the sunrise; it’s as anti-science as can be. Not only is that process inevitable; it’s cruel to curse all deaths, because death is often merciful. Those who say that every death is avoidable and tragic were—and are—speaking insincere, dysfunctional nonsense.

Throughout the Scamdemic, phoniness and opportunism animated the sorrow and outrage that people pretended to feel about the deaths of old, sick strangers. Politicians and the media were the most likely to feign such sorrow. During his campaign, Biden ludicrously asserted that all 200,000 people who had been, by August, 2020, said to have died of Covid “would still be alive” if Trump had done a better job. Those who died were overwhelmingly old and sick, pre-Coronamania, and were not long for this world. Anyone who paid any attention knew this.

I doubt that neither the demagogic politicians nor other Corona-crazed individuals shed any real tears or even felt a twinge about the deaths of those whom they said the virus was killing. Nor did most of them really believe everyone was at risk. The Scamdemic’s orchestrators knew they were playing the public. But many of the unsmart masses did believe the “tragic” narrative and that the “mitigation” measures would work. Besides, many were happy to get paid to stay home. So the Scam took hold.

Every day, thousands of children in the poorest parts of the world die from malnutrition or malaria. Yet, in contrast to purported Covid deaths of unknown grandmas in nursing homes, Americans seldom, if ever, wring their hands over the deeply unjust, and far more numerous, deaths of kids in Brazil, Bangladesh or Burundi.

—

On the morning following the man’s death at the gardens, the weekly farm market was conducted. Various people who knew that someone unfamiliar had died on the same spot less than 24 hours ago nonetheless talked and laughed loudly, as if nothing had happened the day before. I’m not saying that doing so was wrong, in and of itself, or that being somber would have brought the dead man back to life. If you don’t know someone or didn’t see them die, their death is too abstract to feel acutely.

Yet, these same laughing people were all in on Coronamania. They predicated their 2020-22 worldview, and made oppressive and unreasonable demands on others, based on the naive or insincere notion that every death of every stranger was tragic and avoidable. Oddly, these same people who bemoaned the ostensible Covid deaths of unknown 94-year-old grandmas also fervently advocate assisted suicide and abortion. To them, some types of deaths are not only acceptable; the aforementioned death modalities deserve enthusiastic support.

Two days after his death, the garden decedent’s daughter and granddaughter put two tall, glass-encased, bodega candles on the ground where the man had died. Directly above the candles, they tacked to a pavilion post a piece of 2’ x 3’ lightweight white cardboard, using a Sharpie to write the deceased man’s name and short tributes about what a good father and grandfather he was. They glued onto this makeshift memorial three photos of the man. With his eyes open in the photos, I recognized him. Seeing him looking into the camera, and into his future, while holding a basketball in his high school uniform got to me, briefly. Even though injecting drugs is undeniably risky.

Following the first few deaths attributed to Covid, various governors lamented the loss of “these (nonagenarian) souls.” Their sadness and newfound spirituality struck me as fake because these officials govern as cunning, unscrupulous, secular reductionists and utilitarians. Those who bemoaned the death of the very old and sick during Coronamania are the same people who say that they support integrated public schools but send their kids—if they have any—to private schools where they won’t have minority classmates. They talk the talk in order to persuade themselves and others that they’re virtuous. While they obviously don’t mean what they say, many people are easily deceived.

Iris DeMent wrote and sang an unusually-themed song entitled No Time to Cry. She expresses, and then explains, her numbness when her father died during her adulthood. She knows she can’t bring him back to life and that deaths occur every day, across the globe. She recognizes that death is a part of life and that if she cried about all of these deaths, she couldn’t carry on her own life and support other, living people.

Ultimately, not all deaths are equally tragic. What does a society do—insincerely and futilely—in the name of trying to keep everyone alive for every last day? Instead of citing grossly inflated Covid death tolls, locking down, pushing unneeded and harmful shots and wasting trillions of dollars in a phony effort to slightly extend the lives of those who were very old or sick, it would have been infinitely more just and realistic to let healthy people live normally and thrive, while they still could.

Mark, i think your writing gets better and better and this post is raw and compelling.

Agree we way overuse and incorrectly use “tragic” as a death descriptor, but i do think “any man’s death diminishes me” (John Donne) because it reminds that time, and with it deaths, moves me closer to my own last breath.

A great post. So much truth about life and the lies that so many tell. All socialist ideologies are death cults and they are all the same or very similar, as Hitler observed. That's why they all practice abortion, euthanasia, and economic policies that results in death for so many. As you point out, the very people who preen and moralize about certain deaths support policies that guarantee suffering and death of others, the mRNA injections being the most recent vehicle, but a more subtle one.

I thank you for your steadfast work in your community, and your writings. The huge surge in excess deaths all over the world is not by accident but by design and it's only going to get worse. Keep writing the truth, so those who are willing to read them can spread the word about this series of disasters and help others through it all.

Danny Huckabee